AI’s Value for Litigation Experts

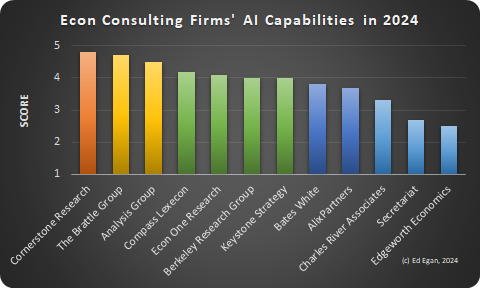

This article compares 12 US economic consulting firms’ Artificial Intelligence (“AI”) capabilities, particularly those used to support litigation engagements. It uses the umbrella term AI to include Machine Learning (“ML”), computational economics, and other modern computer science methods.1

In litigation engagements, leveraging AI can create valuable additional insights and reduce analysis costs, increasing the chances of winning a case and making cases more profitable. So, it is unsurprising that around half of US economic consulting firms have begun hiring in-house engineers and scientists and adding new management to embrace modern computer science methods to support their antitrust, bankruptcy, IP, M&A, securities, regulatory, and other practices.

The integration of AI in litigation, disputes and investigations has undoubtedly altered legal practices, offering unprecedented efficiencies and findings.

Jon Chan, Senior Managing Director, FTI Consultants

The State of Economic Consultants’ AI Capabilities

Economic consultants’ AI capabilities for litigation currently appear nascent and mixed. None of the firms I reviewed had anything like McKinsey’s Quantum Black, BCG’s X, Bain’s Vector Digital, or even FTI’s Digital, which are closer to the Big Four Accounting Firm‘s AI groups and joint ventures.2

Nevertheless, economic consulting firms do seem to be racing to build AI capabilities.

Almost all economic consulting firms now have big data analytics capabilities (in-house or in the cloud), most offer data visualization, and around half have used some AI, broadly defined. Among those using AI, the most popular application was Natural Language Processing (NLP) for semantic or sentiment analysis. Likewise, around a third of firms have performed ML-based optimizations or simulations or offer predictive analytics. Out of the 12 firms I reviewed, four mention generative AI, three mention geospatial analysis, and just one mentions Bayesian methods.

Cornerstone recently started the first applied research group in this area, and, at present, just three firms – Cornerstone, Brattle, and AG – have material AI capabilities. However, none appear to fully understand the very large and rapidly expanding AI space. Keystone‘s recent aggressive hiring might change things over the next few years, either directly or (more likely) by spurring competition, but it is starting as one of the smallest firms. For now, the best economic consulting AI group is still learning to use modern methods; they are far from contributing to their development.

Ranking Economic Consultants’ AI Capabilities

The table below ranks 12 US economic consulting firms using a subjective score from one to five to measure their AI capabilities in litigation support. (See the Methodology section for more information). The table doesn’t include NERA or HKA because I couldn’t find any information about their AI efforts in any context.

| Rank | Score | Firm | Est. Employees | Group/Center |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.8 | Cornerstone Research | 700+ | Data Science Center, Applied Research Center |

| 2 | 4.7 | The Brattle Group | 500+ | Data Analytics |

| 3 | 4.5 | Analysis Group | 1,200+ | Data Science & Statistics |

| 4 | 4.2 | Compass Lexecon | 800+ | Data Science |

| 5 | 4.1 | Econ One Research | 100+ | Data Analytics |

| 6 | 4* | Berkeley Research Group | 1,200+ | AI/ML |

| 6 | 4* | Keystone Strategy | 150+ | Core AI |

| 8 | 3.8 | Bates White | 300+ | Data Science & Statistics |

| 9 | 3.7 | AlixPartners | 2,000+ | Artificial Intelligence |

| 10 | 3.3** | Charles River Associates | 800+ | Analytics |

| 11 | 2.7** | Secretariat | 300+ | Data Analytics & Strategy |

| 12 | 2.5 | Edgeworth Economics | 100+ | Data Analytics |

*Score is based mainly on private knowledge.

**Score is driven primarily by the lack of readily available material online.

The subjective scores fall somewhat naturally into four groups:

- Cornerstone, Brattle, and AG are in the leading group and have material AI capabilities;

- Compass, Econ One, BRG, and Keystone are in the second group and are rapidly developing AI capabilities;

- Bates White and AlixPartners are in the third group with nascent AI capabilities, at least for litigation support;

- And the remaining firms either have yet to enter the race or do not publicly disclose their capabilities.

The Best AI Capabilities: Cornerstone

Cornerstone Research stands out from the other economic consulting firms with its two Centers of Excellence, one in Data Science and the other in Applied Research. These centers support every aspect of Cornerstone’s business, and I quickly found many clear descriptions of how they have used cutting-edge AI/ML to support litigation.

Although Cornerstone was one of just two firms that provided content mentioning neural network transformers as a building block technology, there’s a strong sense of early days. For example, their Applied Research Center, which has a (small) team of in-house data science PhDs, doesn’t mention any academic experts in AI/ML, computational economics, Bayesian statistics, information theory, or related fields.

The subject matter experts at our Applied Research Center work closely with the data scientists at our Data Science Center on critical issues surrounding AI, including using AI methods to produce new evidence on cases, and understanding its implications on the policy and litigation landscape.

Cornerstone Research, Applied Research Center

The Next Best: Brattle and AG

The Brattle Group and Analysis Group (AG) were the next clear leaders among economic consultants in adopting and using AI methods. They appear not far behind Cornerstone and may be competitive or even ahead, but their offerings, especially AG’s, are less well-branded.

Both Brattle and AG were explicit that they integrate their AI capabilities across their practices and provided good examples for litigation support.

These statistical techniques [including machine learning, natural language processing (NLP), and data visualization] can be applied in litigation related to antitrust and competition; intellectual property; general causation assessment; and securities, financial products, and institutions; among other areas.

Analysis Group, Data Science & Statistical Modeling

Brattle and AG have used NLP and related technologies extensively, and it seems likely that consideration of their application to litigation is now well practiced. However, the application of other AI/ML technologies seemed less systematic. Brattle has used simulations and generative AI; AG has done projects using optimization and predictive analytics.

The Rest: A Scattering of AI Capabilities

From Compass Lexicon in 4th place down to Keystone Strategy in 8th, these economic consultants provide only a scattering of AI capabilities and notably fewer litigation support applications.

- Compass’s Data Science page has a nice diagram, three other media items, and nine sentences of text. Even with a picture worth 1,000 words, it is underwhelming. However, if you search hard enough, you can find useful descriptions of their work using Big Data, NLP, LLMs, and GIS.

- Econ One‘s Data Analytics page has lots of text and images, hitting a fair number of the terms of interest, but is light on semantic content. Its blog posts are in the same vein.

- BRG‘s Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning page has an asterisk next to its “Our Experience” heading, which leads to a footnote saying, “Includes professionals’ experience prior to joining BRG.” Nevertheless, BRG has been hiring AI and data engineers in recent months. (It hasn’t announced new leadership in AI as yet.). BRG is a firm that understands dynamic capabilities and absorptive capacity; as the third biggest economic consultancy in the sample, it is one to watch.3

- Keystone has a press release describing its new Core AI group, which launched in 2023. Three former Amazon executives lead the group: Pat Bajari directs the economic experts, Devesh Mishra presides over the technologists, and Aarif Nakhooda is the finance chief. Keystone states that Core AI supports clients of their Global Economic and Technology Advisory (ETA) group. Anecdotally, however, they are currently working on forecasting and big data projects for strategy clients.

On the Bench: Yet to Embrace AI

With scores below four, I rate the next two economic consultants as “on the bench” for their AI capabilities for litigation.

Bates White appears to be the best of this set. Its Data Science page links to five topic area pages, four with case highlights. The pages have good, concise writeups and settlement descriptions. Bates White leverages high-level products from Google, Amazon, Apache, Adobe, and others rather than building things in-house. However, the products they have used are often five to ten years behind the frontier, and AI/ML doesn’t get a mention.

AlixPartners is a stark contrast to Bates White. The page advertising its AI division says AI/ML everywhere and mentions optimization, predictive analytics, and Bayesian methods (yay!). However, AlixPartners’ Economic Consulting team, which falls under its Investigations, Disputes & Advisory Services practice, only makes vague allusions to its use of modern methods.

No AI or Too Little Information

The final three economic consultants either haven’t embraced AI or don’t provide helpful information about their use of modern methods.

Charles River Associates‘ Analytics in Disputes & Investigations page has remained unchanged since January 2021, and Secretariat‘s website is in flux after a series of acquisitions.4 Both firms surely have much greater sophistication than the support for “big data and algorithms” that their websites imply.5 However, I couldn’t find AI engineer job postings or other indications of developing capabilities either.

CRA expertly tackles the daunting volume of social media by employing unique social media analytics tools which efficiently and algorithmically capture relevant information to provide our clients with a deeper understanding of topics and individual subjects of investigation.

CRA, Analytics in Disputes & Investigations

Edgeworth Economics is the only consultancy that mentions working with decommissioned mainframes.6 If you need to access some “big” data from the 1950s, these are your people.

We have extensive experience and expertise working with a variety of systems, including decommissioned mainframes, legacy systems, SAP, and Oracle.

Edgeworth Economics, Data Analytics in Litigation and Compliance

Finally, I couldn’t find any helpful information about AI/ML use at NERA or HKA, so I omitted them from this analysis.

Methodology

I generated a list of US economic consulting firms providing economic experts for litigation and used Perplexity.ai to estimate their employees.7 I excluded firms with less than 100 employees. I also excluded management consulting, accounting, or other firms with a primary purpose other than economic consulting, although such firms often provide economic litigation experts. If a firm is missing, please let me know.

I reviewed each firm’s AI/ML capabilities, partnerships, and experts, focusing on whether and how they had applied AI/ML in litigation support. In most cases, my assessment was based on a review of a firm’s web pages, LinkedIn pages, and other publicly available information. However, I had some private knowledge of firms’ efforts in a few cases, particularly for Keystone and BRG.

I assigned each firm’s AI capabilities a subjective score on a scale of one to five, with five being the best. No firm got a one because of grade inflation. Online information can be outdated and incomplete, so these scores represent the firm’s apparent capabilities rather than actual ones. Nevertheless, they contain valuable information, especially in conjunction with the text descriptions and links.

I was particularly interested in specific capabilities: AI (including ANNs, generative AI, etc.), Machine Learning (“ML”), computational economics, predictive analytics, Big Data, cloud computing, optimization, simulation, geospatial or GIS, visualization, NLP (including content/sentiment analysis, use of LLMs, applications to eDiscovery, etc.), unstructured/semi-structured/structured data, and so forth. In general, the more terms a firm mentioned, the more coherent and detailed they were in their explanations, and the greater the evidence that they have actually used the technology to support litigation, the higher their score.8

Footnotes

- There’s a great debate on nomenclature around AI, ML, computational economics, predictive analytics, (big) data science, and other technologies. The distinction matters for economic consultants, particularly those supporting the litigation process, as they enhance or argue economic efficiency, profit, and welfare; their foundation is truth grounded in economics. Nevertheless, AI is a de facto standard umbrella term, and black-box AIs, like LLMs, can create measures used in meaningful economic analyses. ↩︎

- Economic consultancies are smaller firms with a few hundred to several thousand employees. In contrast, management consultants have tens of thousands of employees, and the accounts have hundreds of thousands. ↩︎

- BRG’s eDiscovery service was developed in-house before many component tools became available as online services, suggesting deep capabilities in this space. ↩︎

- Secretariat acquired Economists Incorporated in July 2021 and Intensity Corporation in Feb 2023. ↩︎

- I found CRA’s AI page, their eDiscovery service, and a page discussing a merger simulation model. For Secretariat, I found evidence of big data capabilities, their eDiscovery, and merger simulation services. ↩︎

- NASA powered down its last mainframe in 2012, three years before OpenAI was founded. ↩︎

- It was clear that some of Perplexity’s employee counts were out-of-date, but I couldn’t readily find anything that was better without a subscription. ↩︎

- I treated some terms as partially relevant – for example, almost half of all firms mentioned doing merger simulations, which generally do not require modern AI/ML. ↩︎

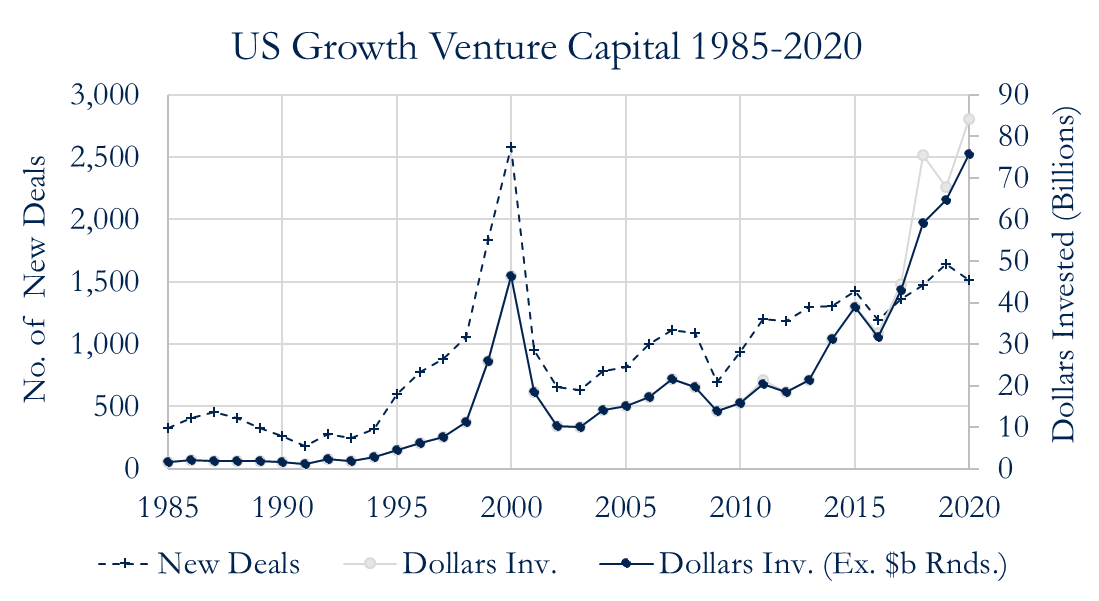

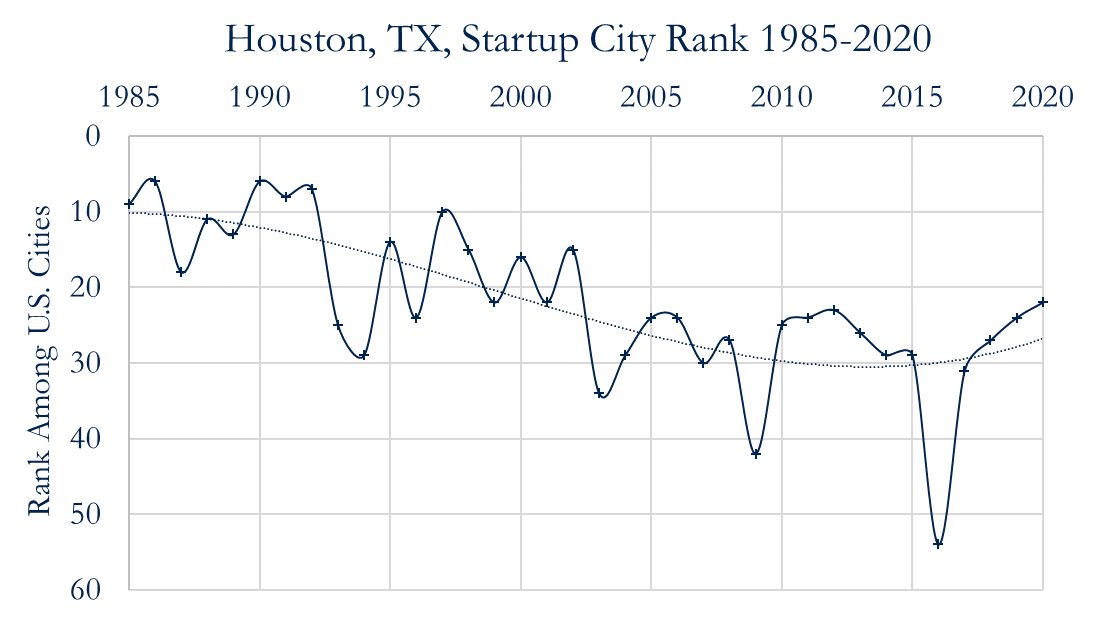

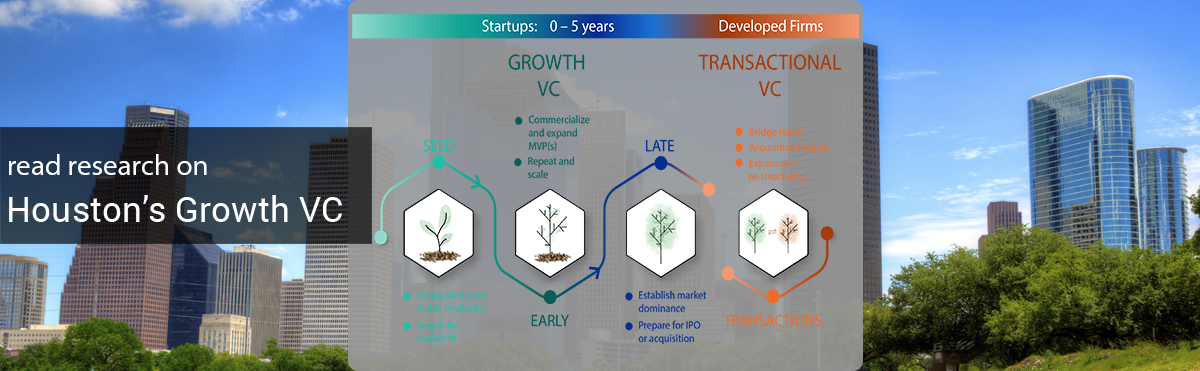

Houston’s high-tech ecosystem can only flourish if it attracts more growth venture capital investments, according to the latest McNair Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation issue brief, “

Houston’s high-tech ecosystem can only flourish if it attracts more growth venture capital investments, according to the latest McNair Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation issue brief, “